Review and Reflections: Cathi Unsworth’s Season of the Witch: the Book of Goth, Nine Eight Books, 2023; or, Why I Never Became a Goth

Mike Diboll

To the memory of L, S, and Pete de Frietas, and to the resilience of Marc Almond – there but for Grace go I.

Prologue

This extended essay is in three parts: a review; reflections on the music scene as I know it roughly 1978-’83 in relation to the book, and; my reflections on the music and subculture covered in the book after I left post-Punk subculture behind me, covering more of less the years 1983-’93. In parts two and three, reflections on my life are italicised, some are accurate reportage of events, some to a greater or lesser degree fictionalised but based on real experiences, a couple are pure fantasy, but relating to the music concerned. Some of my reflective material below is quite personal, but I hope it will be of interest as a kind of case study, and shed light on Cathi Unsworth’s excellent book. I had intended this to be much shorter, around 5,000 words, but as I wrote it grew and grew as the memories flooded back, and I learned so much from the author about the music I had only just missed being a part of.

The subtitle ‘Why I never became a Goth’ is tongue-in-cheek. Perhaps it might function as click-bait, with readers eager to feast vicariously on anti-Goth rants, ‘Bloody Goths, coming over here …!’ There are no such rants below: a more accurate subtitle might be ‘How I never became a Goth’, ‘how’ questions, I find, can be intrinsically more interesting than ‘why’ questions, which often function to apportion or to divert blame, or lead either to self-justification, or the disparagement of others, usually in ‘out’-groups. The historian of the 1914-18 Great War Christopher Clark makes this point well in his magisterial Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914, notice the ‘how’:

‘[This book] is concerned less with why the war happened as with how it came about. Questions of how and why are logically inseparable, but lead us in different directions. The question of how invites us to look closely at the sequences of interactions that produced certain outcomes. By contrast the question of why invites us to go in search of remote and categorical causes: imperialism, nationalism, armaments, alliances, high finance, ideas of national honour, the mechanics of mobilisation. The Why? approach brings a certain analytical clarity, but it also has a certain distorting effect, because it creates the illusion of a steady build up of causal pressure … The story this book tells is, by contrast, saturated with agency.’ (p. xxv11)

Yes, the imperatives of eyeballs on screens notwithstanding, the sheer messiness of the subcultures of the 1978-1993 day tends to privilege ‘how’ over ‘why’.

Part 1

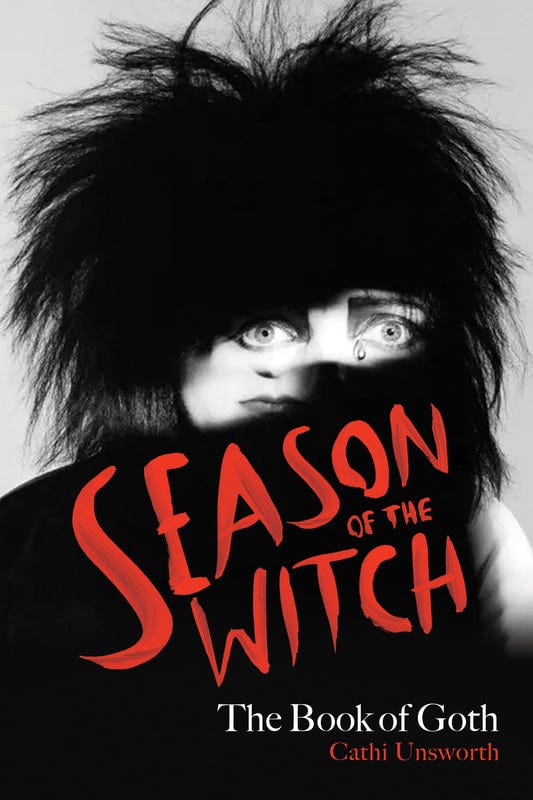

Season of the Witch: The Book of Goth, by novelist, biographer, historian, long-time Sounds journalist and life-long Goth Cathi Unsworth presents the reader with an extensive history of the subculture from its embryonic becomings as a form of post-Punk in the late 1970s in the pulsating heart-beat darkness of the clubs and recording studios of Leeds, London, and Manchester, up until roughly the mid-1990s, via excursions to Australia, Germany, and the USA: London’s East end and Ladbroke Grove, NYC’s Lower East Side, the arty and druggie parts of Melbourne, West Berlin before the Wall-fall, and beyond. This substantial volume of some five hundred pages is also something of an encyclopaedia of Goth, as after the main chapters comes detailed chapter-by-chapter section with cleverly annotated suggestions for ‘Midnight Movies’, a filmography of Goth, and ‘Building a Gothic Library’, a Goth bibliography. These are very thorough and taking in only a quarter of what she suggests would represent a substantial education in Goth that would take the reader well beyond the boundaries of those subcultural staples, music and fashion (Unsworth studied at the London College of Fashion before she wrote at Sounds). The Acknowledgements section reads like a Who’s Who of Goth survivors, while in the Epilogue, ‘The Black Mass’, eyes water as heart attacks, strokes, cancers of lungs, livers and pancreases, overdoses, accidents on two or four wheels, and suicides enable the Grim Reaper to cut a swathe through participants few, if any, of whom had ‘My Body Is My Temple’ as their mantra. The reader is reminded of who has been lost, what lives on in audio and video, and one’s own mortality with its imperative ‘Get on with it!’, carpe the diems I know I have squandered, as I dive down into the past clutching the rusted iron chains of memory.

Each chapter concludes with an italicised section giving an overview of the life and works of a ‘Gothfather’ and a ‘Gothmother’, seldom a Goth in the subcultural sense, rather a historical writer or artist or singer or actor whose work has fed into and enriched the subsequent subculture. Some are obvious choices, Aleister Crowley or Edgar Allan Poe, others less so: Maria Callas, Juliette Gréco, the Brontë sisters, Aubery Beadsley, Link Wray. These sections break up the chapters nicely, and are educative. The book is thoroughly indexed, but largely a name index some thematic indexing would enhance it as a work of reference. A book like this cries out for images, but it has none, apart from the striking cover art. However, the reader does not miss images, and their absence is perhaps for the better, as it forces the reader, or at least the reader of a certain age, to recall sounds, times, places, faces from memory. While with early Punk, at least in the UK, for every authentic guttersnipe there was at least one art college graduate, the post-Punk world from which Goth emerged was powerfully autodidactic. Yes, there were still art school grads (no bad thing), but we all read, relative to what was available, broadly and deeply. Unsworth captures this self-learned and self-learning world almost perfectly, in a way that many similar books do not or cannot.

The main body of the book consists of, (super)naturally, thirteen chapters, each focusing on a handful of bands and solo artists, each arranged more or less chronologically. These chapters treat the reader to a very extensive discography of not only Goth, buts its many influences, parallels, and spin-offs. I skimmed through the book as a first reading, then reread it carefully in depth. As I did so I found myself thumbing through my record collection, and where that wouldn’t suffice resorting to YouTube. Doing so I heard much from bands that across the decades have been my familiars, notably Joy Division and Magazine (being Shot by Both Sides, sometimes literally has become the on-going experience of a lifetime); but perhaps an even more significant discovery reading this book is encountering the music with which I had either been totally ignorant, or which through reading the book I was obliged to reappraise, sometimes decades after first hearing it, either live or on vinyl: the Cramps and Suicide are cases in point – to my shame I recalled I was once a stupid young punk who hassled them when they supported what I at that time considered proper Punk bands. We live and learn. Yet what amounts to a substantial discography is very well integrated into the writer’s narrative in a way that seldom seems list-y. Rather, the narrative grips, but one learns as one reads and one’s learning through reading is interrupted and enriched by the necessity of listening. This is how books like this should be, and it is cleverly structured.

The book has two other aspects: memoir and social history. The Prologue and the Epilogue, the former ending ‘I became a Goth’, and the latter ending ‘I am a Goth’ are quite personal in the first we find the author as a shy an booky adolescent living in a remote rural Norfolk cottage reading Dennis Wheatley’s occult pulp fiction and hearing the Banshees on the John Peel Show as ‘… the old house began to clank its pipes, the wind moaning back across the flat fields and whistling through the roof tiles to the accompanying lament from the fog horn from Yarmouth harbour and the gnarled fingers of the old willow tree behind my bedroom tap-tapping on the window pane’. I am reminded of my daughter Rebecca (the artist known as Hyd, rhymes with ‘hide’), now fifteen, in her small timber-framed bedroom in our Sussex cottage with its leaded windows: replete with many spiders and their webs her US friends say that it looks like it’s Halloween all year round. It has a sixty-foot well in the garden from the time there were no utilities coming into the house and a cess-pit, the water-in company resorted to a water diviner to find the later Victorian piping to meter the in-flow, marks of makers long dead adorn ancient joists, under the floor boards can be found witch bottles stuffed with nails. My youngest daughter Rebecca, 15, identifies as Emo. In Season’s Epilogue we find Unsworth reflecting forty years on not merely upon what Goth has taught her, but on a life lived in Goth, ‘So if anyone picks on you for being different in anyway, please use this book to hit them on the head with and rest assured you are in good company’ – Becca like me is neurodivergent and she proudly rejects heteronormativity – ‘Goth has been ridiculed derided over the decades [like its parent, Punk] for being miserable, morose and moronic – but it is anything but. It stands for all the essential forces of creativity, friendship and vision, not to mention humour, it’s just that until things get brighter, it’ll mostly be wearing black.’

Within the thirteen main chapters, the authorial voice is different, the ‘I’ is mostly replaced by the objective third person of the narrator of history. Mostly: as Cathi comes of age in the Goth scene emerging as a participant, the “I” begins to weave in and out of the narrative, but never obtrusively, rather authoritatively. It is quite startling when this is first done. As we read further into the book, it reads increasingly journalistic as her career, further into her Goth journey, takes her to Sounds, in this sense there is an autoethnographic sub-strand to the book. Very generously she cites quotations from her colleagues in the holy trinity of the mainstream music press of the day, Melody Maker, New Musical Express, and Sounds, to great effect and affect. Having read a fair bit of academic books recently, it is a relief to read an extended text not printer’s bedevilled by Chicago Style footnoting or Harvard or Modern Language Association Style in-text citations. Academic friends might cite the imperative of source verification, but like all good extended journalism Cathi’s book is implacably cited in the endnotes, it’s just not in the reader’s face, spoiling the read. Then there is the humour. Playing-with-language puns, irony and in-jokes abound. When I have tried to do that writing academically about Punk (broadly defined) editors frown on it. Their loss. One ought, even academically, write playfully about Punk: if one were writing sociologically about, say, the religious and far-right radicalisation of young people in schools (as I have), a distanced and objectivist tone is required, but writing about subculture? Unsworth’s tone is spot-on. Even with death, nobody ‘dies’ or is ‘killed’: people don’t merely ‘pass on’ or ‘away’ either, they ‘pass through the veil’, or in the case of the Cramps’ Lux Interior ‘rockets into the great beyond’ aged sixty-two. This is not mere euphemism, but the perspective of a writer who celebrates life, yet anticipates a mystery beyond it. The causes of death are recorded with Gothic morgue-slab accuracy, an aortic dissection, hypoxia leading to dystonia and a fatal heart attack, a blood clot on the brain as a complication of cirrhosis. Bunnyman Pete de Freitas died in a head-on on his bike in 1989 at that fated age of 27. But this was a generation born when ‘straight edge’ meant the side of a wooden Made in England twelve-inch ruler (the inches divided into sixteenths) that was used for pencil (the bevelled edge was used for ink); as Unsworth quotes Gun Club’s Jeffrey Lee Peirce, who died of a cerebral haemorrhage aged 37 in 1936, ‘When the body is finished then good, it’s used up like an old car. Into the breaker’s yard with it and on to another one’.

But the social-historical stand in the nook’s weave is also important. The ‘witch’ in question is Thatcher, and in extension Thatcherism, monetarism, neoliberalism, Reaganomics, the New Right, call it what you will. Also the reheating of the Cold War, its malign influence on those who lived their youths in the shadow of a seemingly immanent mushroom cloud should not be underestimated. Nevertheless, Unsworth’s Thatcher is not quite the ogress of lefty demonology, she’s a witch who summons the demon of the supposedly ‘free’ market, not the demon itself. Thatcher’s relatively humble background (relative to that of most Tory MPs of that day), her struggles to be taken seriously as a woman politician, and her formative years in which her ideology crystalised are treated with some sympathy: she is treated as a figure who rose to prominence in the troubled times of the 1970s -- the Sex Pistols too bemoaned the prospect of ‘another council tenancy’ as an aspect of a world in which there seemed to be ‘No Future’, later Crass’ ‘there is no authority but yourself’ would find echo in Thatcher’s ‘there is no such thing as society, Thatchergate, perhaps an early attempt at ‘fake news’, notwithstanding. Astutely, Unsworth weaves the rise of Thatcher with that of Malcolm McLaren.

In the Epilogue the hubris and inevitable fall of Thatcher is treated as much with lament as with celebration. Her going was more a merciful release, yet I concur with the author that those who came after her, Blair, Cameron, Johnson, were worse. In particular, Blair unleashed an illegal war of aggression that cost millions of lives and destabilised an entire region, something his successors have yet to do. That he and the other Alastair, a figure far more a demon from the Qlippoth than poor old showman cum psychonaut before his time Crowley ever was, are so rehabilitated surely shows how, in Britain’s toxified political-media ecosystem Brown Lives Don’t Matter. Blairism built on Thatcher’s personality cult to make of what was once the primus inter pares office of Prime Minister into an unconstitutional cod-Presidency, he entrenched the notion of a populist party, New Labour as ‘the political will of the British people’, the Thatcherite harassment of the non-working intensified under Blair’s New Party so that Tax Credits subsidised employers paying poverty wages, the demonisation of refugees and asylum seekers began back then: Britain was once proud to welcome people who were once called ‘political refugees’. Without Blair perhaps Johnson, even Trump, would have been unthinkable.

But I should not be diverted into a political rant. Cathi Unsworth is no Thatcherite, ‘Goth in the time of Thatcher was a kind of resistance against stupidity and ignorance’, such as that displayed by the political right of the 1980s over AIDS: her narrative of Goth is interwoven with the histories of the Miners’ Strike, the printworkers strike, the Battle of the Beanfield, Greenham Common. The book opens with the so-called Winter of Discontent 1978-9, murder of antiracist activist Blair Peach by the Metropolitan Police’s Special Patrol Group, the Irish National Liberation Army’s assassination of Thatcher confidant Airey Neave. Peter Sutcliff, the serial killer dubbed by the tabloid press as the ‘Yorkshire Ripper’ haunts the North where, along with London, proto-Goth would emerge. The narrative closes with the 1990 uprising against the Poll Tax and the subsequent fall of Thatcher. However, the politics in the book do not mean that the writing about Goth is merely a front, SWP style, for political polemics. The writing about politics is generally concise, historically accurate, and to its point of presenting the political-economic contexts of Goth’s emergence. Unsworth is generous to her ‘witch’, and insightful in seeing in Thatcher’s womanhood an ability to relate to both Reagan and Gorbachev, bringing the heated-up Cold War to a more peaceful conclusion in the way that no male world leader could have done at that time, ‘perhaps the woman described by France’s President Mitterrand as “having the eyes of Stalin and the mouth of Marylin Monroe” was uniquely able to act as a bridge between the two superpowers’. Unsworth may well be right in this, although what followed in the former Soviet sphere was a triumphalist neoliberal sell-off fest that spawned another monster, Putin. But at least ‘the end of Thatcher’s term in office did not finish in the total nuclear annihilation of the planet, as most of us ‘80s kids feared it would.’ Yet as Unsworth’s narrative concludes, the demonic figure of Rupert Murdoch looms ever larger, Thatcher has sorcerer’s apprentice. Against such mass-media moronising she rightly stresses how Goth was ‘elitist’, seeking to rescue that word from the lowest common denominator populism of the political-media environment that Murdoch did so much to forge, ‘it feasted on high art, challenging literature, sublime discourse, and intelligent conversation. This book deserves a sequel, perhaps charting how Goth develops from the mid-1990s up to now, perhaps a Winter of the Warlock?

Part 2

I’ll pause for a moment to consider my stance in relation to the subcultural scene so skilfully evoked in Season of the Witch. I have never identified, or even thought of myself, as a Goth. In some respects it is surprising that I never did. My mother was an occultist and under her tutelage I read and explored quite broadly and deeply in the Kabbalah and in Magic, as well as the more usual tarot and astrology. If first read Crowley when I was thirteen. I was shy, introverted and bookish, and the reading of my early teens spanned Mailer to Mishima, Dostoyevsky to Debord, Graves to Gramsci, Freud and Marx, the scriptures of the worlds’ faiths, Beowulf to the Modernists via the Romantics. My father was a far more practical man, and from an early age got me into motorbikes and biking. I still ride today after a half century. So my entry into the world of early Punk was presaged by violent death: in May 1976 I witnessed a high speed motorcycle accident where two of my best school friends were killed before my eyes in a head-on collision with a car that had a closing speed of about 140mph, this happened at dusk down an unlit Kentish country lane, I was riding behind them and was a witness at their inquest. A nice bike, ’72 Suzuki T250. ‘Watch the muscles twitch’, those images came to mind when, a couple of years later I bougtht that album – our little group of proto-Punk biker schoolboys scaped the money together for a floral tribute in ivory white and electric blue-green, the bike’s very early ‘70s colours, with orange in each corner for the indicators, L live for bikes, he would have appreciated that, RIP S and L. In those days there was really no such thing as counselling, or any real understanding of teenage trauma, the prevailing attitude of the teachers was ‘well, that will teach you lot not to mess around on bikes’. My trauma went untreated and by July I had dropped out of sixth form after an altercation with a teacher. I had no plans as to what to do next, and drifted into Punk. London was only twenty-odd miles up the road, why not? For much of the time, I’d not really do much, just sit autistically and watch the Punk spectacle swirl around me. I was one of the quiet ones at the back.

With post-Punk I became more involved in the scene, the bands that attracted me strongly were precisely those that feature in the first two chapters of Season: Joy Division, Magazine, the early Cure, later Killing Joke. I loved the Banshee’s sound but there was something about the lyrics and the aesthetics that never quite did it for me. But with a neurology that inclined me to see the world quite differently to most, and painfully acute sense of the precarity of life and the imminence of death, disfigurement, and mutilation even amid joy, I was deeply attracted to the darkness of that music, the existential bent that was unafraid to question and contort that which we were all expected to take for granted, to drink in with gusto the poison in our human machines, to pet the tarantula in the box of bananas, the willingness to expose how the worse nightmares were not to be found within the unconscious subjectivity of our dreams, but in the ‘normal’ objective world around us that we supposed to take at face value.

Nevertheless, I felt something was missing. Having preferred the Clash to the Sex Pistols, I felt an equally strong attraction to the idealistic and the utopian, particularly with regard to social justice, and particularly regarding racism: the Punk swastika had always sickened me. I’d thus follow the Ruts and the Upstarts, listen to the militant reggae of the day. I guess I squared the circle between what one might now call proto-Goth and politically engaged, explicitly left-wing Punk through Anarcho-Punk. I never heard that term in the day, we were simply Anarchist Punks. I played a small but significant part in the emergence of that subculture, my ‘zine Toxic Grafity ran from 1978 to 1982, at its height selling in the tens of thousands, due in no small part to the Crass flexi-disc in the Spring issue of 1980. But early Anarcho- was quite different to what it would have become by the mid-1980s, the association with political anarchisms was much closer, its relationship to other post-Punk scenes more open than would later be the case, the emphasis was far more on different forms of political activism, including its more violent forms, the anti-fascist element stronger, and far less emphasis on the pacifism, individualism, and vegetarianism that later would come almost to define it.

Toxic soon left behind the more conventional fanzine format of band interviews and gig and album reviews. Instead, it sought to express the aesthetics, attitudes, ethics, and politics of early Anarcho through rant, drawing, collage, symbols, poetry, prose essays, and prose poetry. It was no longer part of the DIY music press, but band would submit artworks. Subtitled A Reality of Horror it retained in images and writing a fascination with the Dark Side, the macabre, the perverse and perverted. There was as much of the aesthetics of Throbbing Gristle about it as there was about the politics of Crass (it didn’t feature the Crass logo, it had its own ones). Then one day. When my balloon is pricked it doesn’t fly crazily about the room flapping and farting out air until it is empty, it explodes. When my vessel is overfilled it shatters into myriad shards the fall into the darkness and it takes a lifetime to recover them. One day I was coming back from Dial House on public transport in the summer of 1982 and a thought came to me at random, ‘This is going nowhere, it is doing no good. I will never go back there’. And I never did, to this day. There had been no argument or row, indeed the apparent randomness of that thought seemed to confirm its existential veracity. So I stopped having anything to do with those bands, I stopped Toxic. Within eighteen months I had stopped going to gigs completely, I cut myself off from any form of post-Punk, almost any kind of music, to do totally different things with my life. The next time I would go to a punk gig would be 2013.

My Punk consciousness returned as a kind of epiphany, as I witnessed student uprisings and the shooting dead of unarmed protestors during the Arab Spring. In that sense, my Punk subjectivity was formed between two different sets of blood and brains on the pavement, those of 1976, and those of 2011. So that is why I never became a Goth: suddenly, abruptly, I disassociated from any post-Punk scene completely. Had I merely became disillusioned with Anarcho, I would have inhabited the Batcave. But I didn’t. Part of me wishes I had. This is what, for me personally, makes Season such an interesting read. I can summon forth in my memory scenes from gigs at which the bands the book explores played up until about early 1983. After that, it is a blank, I am reading about a scene from forty years ago that I had nothing to do with and about which I know little, and most of what I do know was gleaned well after the event. It feels like a form of amnesia; but it isn’t, I simply wasn’t there. Season is a guide to my Road Not Taken. So I back the steering column shifter of my battered old pickup truck into reverse and looking over my shoulder go back over the bumps to the fork in the road.

There is so much I could say about Joy Division, but so much has been written about them too. So I shan’t say much here as there’s not a lot I could meaningfully add. Suffice to say that dodgy name notwithstanding they have been part of the soundtrack of my life more or less continuously since I first heard them in 1979. And listening to Sisters of Mercy it is hard to imagine they’d ever have been a thing if it wasn’t for Joy Division. It doesn’t surprise me that Ian Curtis voted Conservative that year, he was such a mass of contradictions, a scryer of the black mirror in the dark night of the soul, but married young and mortgaged young with a respectable job in a perhaps reluctant submission to a conformity he would so meticulously dissect. The Jam made a similar pro-Thatcher statement as I recall, but went on to retract it, Curtis didn’t live to have that option. As with Nirvana it is hard to listen to Joy Division’s output without hearing it as a note roughly scribbled on the kitchen table. I wasn’t surprised at either suicide, indeed I would have surprised if that hadn’t happened, as that suicide seemed somehow to be the capstone of an inverted great pyramid dug deep into the profoundest isolation, as if it were the climax of a work hitherto in progress. If that would callous perhaps that is because suicide is not always a tragedy, sometimes the decision should be respected as a brining to completion. I’ve never seen the point of New Order.

Magazine? As soon as I heard Shot From Both Sides I knew I was hearing something fresh and of great significance, Second Daylight is indeed magisterial and Soap evokes and era of grainy dotted halftone newspaper images of rubble and body parts covered in white sheets, the ink coming off on one’s fingers, ‘I think there is something wrong with my liver’. Chislehurst is about six miles up the A233 from Biggin Hill, where I grew up, the imaginative world of the Banshees had, I had always supposed, similar underpinnings to my own, that precocious autodidacticism, the sense of the horrific lurking, of strings snapping and the bizarre and perverse swept under the rug in that advertisement-vaunted demi-monde of semis. But that ice-crystal cut-glass guitar of John McKay, and Steve Severin’s broody bass, near experimental on intros, often punk-rocky through tracks: human beings out of their element, meaningless, in all the symbols have not meaning … in the impulse is quite meaningless, a cerebral non-event’; I think it’s quite accurate to say that Goth starts here, even if it didn’t yet have a name – and OH! Her voice! Goodbye for ever to a life of simple pleasantries. I used to play the arse off of this. Production like this is it was not for what happened before UK punk.

The sparse intro of ‘Helter Skelter’, then the light-metallic Kallang! of the guitar, the heartbeat drums, the speeded up adrenaline heartbeat as if before committing a murder or a suicide, but for me no: the metallic crispness is the crackle-clang of the expansion chamber exhausts of my tuned to the Nth Yamaha RD400, the giant killing punk biker’s bike of the day, the drum beat my heart in my mouth as I hit the powerband and the wheel lifts in a third gear wheelie, and as that voice begins its chant I’m 20 again, doing 90 in a 30mph zone as I head up the A233 back to London after visiting my now late parents, ‘as I stop, as I go for a ride … as I see you again’.

I’m going down to Biggin Hill to see my parents, we are at a Chinese restaurant by Bromley hospital’t sadly, it wasn’t called ‘Hong Kong Garden’, it should have been. It’s early Autumn ’78. I’m with some mates, we are all on bikes. Mine is my RD400. RD as in ‘Race Developed’. I’ve done so much on this bike, it has shiny new Allspeed pipes, a Stage II road-track tune by Stan ‘The Man’ Stevens at his Brands Hatch workshop, a steering damper against tank-slappers, a box section swinging arm and trick shocks, clip-on bars and rear set foot-rests. I’ve ridden this bike on track and road and I know it’s fucking fast. A few days ago I was on my own going up to London at an Indian restaurant at Market Square Bromley, there was a cool record shop there that was cool to browse. Eating on my own, a lobster vindaloo with a lager, I looked out the window at my bike. It was on its prop-stand outside the restaurant, there had been light rain and the orange sodium lights lit up the bike as if it were a photoshoot for a bike mag. I had a weekend of sex ‘n’ drugs ‘n’ rock ‘n’ roll to look forward to. Fuelling my face with the curry I looked at it and mused, ‘Hey, I’m 19, life doesn’t get any better than this! (It didn’t, actually). But that was a few days ago. On the way back we have an altercation with some Smoothies outside the Chinese. We don’t look right to their eyes. The police are called, separate us, the Smoothies fuck off. I’d had a couple of lager tops and some speed, but the cops weren’t bothered about that. ‘Nobody’s riding home tonight, you hear?’ My mates lock up their bikes. But RDs are piss easy to steal and there’s a market for their parts on the race scene. No way am I going to leave it there. My mates fuck off, so do the cop make a show of it, but I know they’ll be hanging around. I make a show of checking my bike is locked, then shove on my helmet and start up. Ahead is a chocolate brown Rover V8 saloon. Obviously an unmarked cop car. I fire up. I can see the joy in their faces as I fire up. The bike isn’t quite, at all. ‘Fuck you!’ I go past them on a slip road and hear the tyres squeal, on the main road now the chase is on. I jump the read lights by the hospital, and accelerate up the hill. There isn’t a car on the road that can hang with this to 100. But I know they’ll radio ahead. I ride like a demon, full track skills, total focus, take the right that leads to Biggin Hill. Behind me now is another Rover, a V8 Metropolitan Police traffic car in Jam Sandwich livery. I regulate my breathing as if I am on a race track. Stay calm, in the zone. Ahead is a set of lights. They are red for me. Good. It’s night and I can see from the lack of headlights that there is no traffic coming across me. I shoot the lights at 90. A mile or so ahead and a blue Kent Police Rover joins the chase. He’s on my tail as I approach the chicken farm bends. I keep calm. The bends are tight and there is drizzle. I know how to do this, cornering I cog down into the powerband, my rear wheel slips away but knowing how to control it I counter-steer and let the slip carry me through the bend. This is how to ride a two-stroke fast, I’ve seen Barry Sheene, Kenny Roberts, and Steve Baker do it at Brands Hatch. I straighten up past the bends, a road leads to Downe to my left. I decide not to take it. I’ll take advantage of the straight that leads to Leaves Green. Again they have radioed ahead. A Morris 1100 Panda Car tries to block the road, a cops arm waving like crazy. I aim straight at him, I guess at about 120. It’s a risk but I guessed right, he gets out of the way, the car wobbling in my slip-steam. All he has achieved is block the road for the Rover. I can’t hang about, and wring the neck out of the bike past RAF Biggin Hill and Biggin Hill Airport. I seem some bike cops on BMWs going the other way, obviously called in to deal with me. I know this is serious shit. Extreme even by my bike hooligan standards. My lights fuse blows from the vibration, but that’s to my advantage. But I know my main fuse could be next. Then I’d be in serious shit. Past the Airport I approach Apperfield. There’s a new-build housing estate there. I do a left, then a right, then dump my bike on its side behind a bush. A bit on I dump my leathers and crash-hat. Then hide my bike keys under a brick by a street light. I report my bike stolen at a phone box, then stop off at the Black Horse pub for a pint, and resolve to walk the couple of miles to my parents’ house. The road is by now crawling with cops in every kind of vehicles, Met, Kent, and Surrey police. I walk down the valley and up the other side through footpaths I’ve known since childhood. I spy a Kent Police cop at the head of the cul-de-sac where my parents live. I sneak around the estate and scramble over some garage rooves and go into my parent’s house by the back door. They have gone to bed. I pour myself a tumbler of whisky and try to concoct a cover story. An hour later and there is no knock on the door. In the past my dad has provided me with alibies for this sort of thing, but this is extreme. I sleep furtively then go early to the shop about half a mile away on foot. There is a cop car stationed at the head of the cul-de-sac. He scowls at me, I nod and half-smile. That afternoon I recover my bike, half expecting arrest. I take a round trip via Chislehurst, Orpington, Shortlands, and Catford to get back to central London.

I had got away with it this time, but his was extreme, I need to slow down: I realised that the deadly events of May ’76 hadn’t served as a warning to me as the teachers and other adults had hoped, rather I realised that I was traumatised to the degree of having an unconscious death wish, to re-enact the events of that May evening on my own body. So I decide to focus more on the music than bikes, give them a rest for a while: I reason that while post-Punk scenes had their risks, I was far more likely to kill myself on two wheels. One consequence of this is that I became far more actively involved in the Punk scene I had really only spectated. As Punk shattered into the kaleidoscope shards of post-Punk, I became increasingly involved in Anarcho. By 1982 I was back on the bikes, my girlfriend of the day Y was pregnant with my first daughter A. So I was back in the saddle not as a hooligan, but to earn a living.

That cover of Helter Skelter defies verbal description, it can only be expressed by extreme action. Eat metal. I’m sure I’m not the only person with this anecdote, but when I first played The Cure to my mum she really did say ‘Cure? I’d rather have the fucking disease!’ I now live halfway between Crawley and Brighton, Crawley’s changed. My daughter has a Cure hoodie. What was Meursault’s crime? Literary critics have pointed out that it would in the highly racialised context of the colonial Algeria of the 1940s it would be highly unlikely that a pied-noir French Settler would face the guillotine for killing an armed Arab, that his real crime, the crime for which he was beheaded, as a failure to show sufficient remorse over his mother’s death, less a thought-crime but an emotion-crime to the settler patriarchy of that time and place. But I stuck with the Cure over the years – a Slimelight era partner maintained my interest in the Cure, and introduced me in the 1990s (yes, really, I was that out of touch by then) to the Sisters of Mercy . My copy of the much later Disintegration has a huge scratch across ‘Praying for Rain’ from when a year or so ago Horatio, my sliver-tabby Maine Coon cat decided to use the turntable as a roundabout then decided that was not for him.

Two chapters in and I am still on familiar post-Punk territory as narrative Season continues, at that point in my journey I am not quite at the fork in the road. Indeed, I can’t see it yet. Looking back I think about who else might have featured in those two early chapters, the Damned should have figured more prominently in a history of early Goth, I think (although Unsworth will write about them brilliantly in Chapter Ten), and not just because of Dave Vanian’s 1940s vampire look, ‘Fan Club’ explores the psychopathology of fandom referencing teenage suicide, then there’s ‘Drop some blues, time to choose / Why your heart is just a stabbing / Bloody eyes, can describe / The nature of your hacking’ (‘Feel the Pain’), all on a 1977 album that isn’t all the catchy punk love song New Rose. I’ve never been a huge fan of Adam and the Ants at any stage of their career, but their early exploration of kink, fetish and voyeurism surely feeds into proto-Goth? And the Stranglers? That they were a Pub Rock band that parasited on Punk is a fair criticism, although UK Punk owes a larger debt than is often appreciated to pub rock (Dr Feelgood?). It is also fair to say, I think, that they embodied and to a degree promoted a lot of what might today be called Toxic Masculinity (Peaches?) That said, their lyrics summon the strange and the creepy, off moods and dark feelings of vengeance, the dank and poorly lit city streets where stalkers and worse lurk, the artwork to Rattus Norvegicus (1977) is a Gothic country house, and their 1978 cover of Dionne Warwick’s 1964 ‘Walk On By’ superbly captures the sulky, morose wounded pride of the freshly dumped male. Above all, they had a keyboard, a Doors-like one at that, which along with that brooding bass anchors their sound with twisty ropes of dark psychedelic fancy – Jim Morrison is Season’s Gothfather 1. But Unsworth is writing The Book of Goth, not a Book of First Wave UK Punk, so brevity is justified.

With Chapter Three I’m still not yet at the fork in the road, but I know its coming and I can see how the left-hand path trails off into the distant dark forest beyond an outcrop of rock. Pre-Punk, I had been a fan of early Metal, Black Sabbath, Deep Purple, and the heavy rock of Led Zeppelin had been the mainstay of the biker milieu into which I had been initiated, I don’t mean arcane biker gang initiations, but stuff like dong the ton. With Punk I missed that heavy sound, although I think ‘Light Metal’ might accurately describe some early Punk. Light Metal, let’s say lithium. But generally I missed that heaviness, and my craving for bass that sucked the air from my chest was mostly satisfied by Dub Reggae. Along with post-Punk came the New Wave of British Heavy Metal, but I found it puerile: it lacked depth and sophistication, Unsworth rightly upbraids it for its ‘headbanging guitar histrionics and cartoon horror imagery’. In later middle-age I would discover a more mature kind of Metal, by then the genre had split into many sub-genres, some of which I would wholeheartedly embrace, but all that lay decades into the future, back as that fork in the road approach my yearning for heaviness was satisfied by Killing Joke, and, as with Joy Division (I saw them play together), Killing Joke became one of the bands that would provide the soundtrack of my life across the decades from then until now. Season offers several foundation myths for Goth, Just-So stories about how Goth got its name, the first in the book concerns Jaz and Big Paul performing a dark ritual just before placing an ad calling for prospective band members 1979. That may well, be, but I can’t recall hearing ‘Goth’ to describe the music genre or subculture until some years after that. But oh that sound! While following a Crass tour of the south-west, I was in at a pub in Bristol’s St Paul’s in April 1980. As the riot ensued the Afro-Caribbean landlord ignored restrictive the licencing hours of that time, barring the entrance with some fruit machine, ‘Wardance’! A year later and Brixton, Moss Side, and Toxteth were aflame. I was in and out of the anarchist bookshop squat at 121 Railton Road at that time, living at Nettleton Road Short-Life Housing Co-Op, a road of licenced squats a few miles away the other side of the Old Kent Road. For miles around the shops were boarded up with shutter-board and sheets of galvanised corrugated iron, which of course we plastered with graffiti. The album Killing Joke really was for us the soundtrack to those days of riot and hunger. I once joined a picket outside of Downing Street for the Hunger Strikers, hats were passed around for donations for ‘The Boys’ as a police helicopter videoed us.

Looking back, perhaps the cover art, which I thought über-cool in the day, a period photo of youths scrambling over a wall to escape a British Army CS gas attack in 1970s Derry with ‘Killing Joke’ apparently sprayed in large letters on the wall, was gratuitous. Decades later I would see demonstrations ‘cleared’ by masses of CS, thousands of rounds (about 25 were used by the police at Toxteth in ’81) used to weaponize the gas as a chemical weapon so that the streets were littered with used cannisters. Decades later I would see CS rounds fired directly at a protestor’s head with lethal effect. Decades later my new born daughter would be moved to an incubator as CS entered the maternity hospital. Decades later, while studying for a Masters in the Anthropology of Violence I would learn of the ethics of the image and I learnt that is not a cool way to promote a band. But that is the me of the 2020s writing, and I am hurling brickbats at the band from within my glasshouse: back in the day Toxic Grafity was only too eager to use images of the suffering and oppression of others gratuitously to make its point.

With Bauhaus too I am still at a familiar point before the fork in the road, and smiled as I heard ‘Bela Lugosi’s Dead’ when attending the private viewing of The Horror Show! at Somerset House on the Halloween of 2022, and Toxic Grafity and related material was prominently on display near the beginning of the exhibition as visitors filed in. Crowley as Gothfather? ‘He’s Reading Aleister Crowley!’ said Humphrey to the class in mock horror, with shoulder length hair dressed in a purple velvet jacket and emerald green shirt topped by an orange and gold paisley cravat, wearing checked brown and beige flairs and purple Chelsea boots he was our drama teacher, with an eye for the boys. It must have been some time in ’74 and I think I was reading, quite matter-of-factly, Crowley’s novel Moonchild (1917, published 1929), then out as part of the Dennis Wheatley Library of the Occult (1974-77). Previously, Humphrey had given me a low mark in a drama exercise, we had been told to enact Dracula, in my interpretation of the role the Count was rat-like and demonic. Humphrey opined that the character was supposed to have an erect, aristocratic bearing, ‘He’s a Count, for God’s sake!’ He must have been thinking of Christopher Lee, I was channelling Nosferatu, that I’d read about in Films and Filming magazine, which parents got. Moonchild wasn’t my favourite Crowley work, that was an anonymous and early work (1909), Liber 777 Prolegoma Symbolica ad Systemam Sceptico-Mysticae Viae Explicande Fundamentum Hieroglyphicum Scientiae Summae, which largely in tabular form set out to construct a comparative angelology and demonology of the world’s major belief systems arranged in rows in accordance with the ten sephiroth Kabbalistic Tree of Life (Etz Hayyīm) and the letters of the Hebrew alphabet. I read it so avidly as a schoolboy that the spine broke and I had to drill holes through the margin to hold the book together with four pipe-cleaners twisted together in lieu of a binding. When later I discovered the actual Kabbalah -- by which I mean the Zoha (C13th), the work of Moses ben Yakov Cordovero (1522-1570), Isaac ben Solomon Luria (1534-1572), and Baal Shem Tov (1698-1760) -- found out with some disappointment that Crowley’s work was replete various errors and mistakes (again), and leaps of imagination and flights of fancy. Yet 777 created within me a life-long interest in comparative religions and the linguistic and symbolic systems in these are expressed. As I reminisce, it seems very odd to me that I never became a Goth.

Part 3

So the Cramps? ‘Well I was pulling up grade that’s known as the Devil’s Crest / All of 36 ton on a run called the Nitro Express’ … Fantasy me pulls over to swat away the blowflies that inexplicably have started to fill the cab … ‘There was 36 ton of a detonated steel, over eighteen tyres that smoked an’ squealed / I had to ride her down, I couldn’t jump free / or there’d be a big hole where that little town used to be ….’ Red Simpson’s dark truck driver country number ‘Nitro Express’ was on the eight-track, a compilation that included Johnny Cash’s ‘Once Piece at a Time’. I pull over and eject the fat cassette as the picking at the resonator steel guitar fades. I’ve reached the fork in the road. Ahead I can see how the road not taken twists and turns through dark, lush forest, but ahead of me is dusty scrub and prairieland, tumbleweed blows across, a roadrunner starts as I switch off the big old oil-leaking V8. I am low on gas, to my left I see an unmetalled road leading to a tumbledown farmstead. I hear a generator, they have gas. Broke, I’ll offer to do odd jobs for gas. I restart the engine, is starts with a hiss through a leaky head gasket on the left cylinder bank; I knock the steering column shifter into drive and head on up the rocky path, ‘… and it didn’t cost me a dime, I’ll have the only one there is in town ….’ There seems to be nobody at home. I dismount the battered old pickup, walk onto the veranda, ‘Hello, hello!’ I venture through the flyscreen doors, the main door is ajar. I think I see a figure move furtively, ‘Hello!’, gingerly I step inside, gently pushing aside some sort of windchime that seems to be made of chicken and wolf bones. A tall figure has his back to me, he is about to open a grubby old Frigidaire. Arrrgh! A sharp metallic sheen that sounds like the ringing of sheet steel resonating as a circular carborundum saw blade cuts into it. The sheer metal chime fades, then it’s back again, then again!

TV Set. I don’t know why I never quite got the Cramps. I saw them a couple of times, but very oddly neither liked them nor not liked them. That is odd for what surely is the most Marmite of bands. I kind of filed them under not ‘interesting, but not quite me’. I guess it was to do with Anarcho: at that time it hadn’t become quite as didactic, po-faced and preachy as it would become. At that stage it was just ‘earnest’. There was a reason for this: early Punk had a strong streak of nihilism, ‘Get pissed, destroy!’, ‘No future!’, and the gratuitous use of the swastika less out of any neo-Nazi sympathies (although neo-Nazis would very quickly seek to exploit that), but more because it shocked and disgusted the parental and grandparental generation, people who had known, and often went on and on about The War. But post-Punk in its various manifestations was eager to go beyond nihilism, having (from our perspective) ripped the shit out of the system, we wanted to offer an alternative. There were early punk precedents for this, notably from the Clash and later bands that followed in their wake. The Clash also made that transition from the nihilistic to feeling for some kind of solution: from ‘London’s Burning (with Boredom Now)’ to ‘London Calling within two years; from ‘I’m so Bored with the USA’ to Bo Diddly, Rockabilly, and Brand New Cadillac. There was also from the rise of DIY, which began with the Buzzcocks’ Spiral Scratch EP (1977). The alternative was left-wing, very much so with early Anarchist Punk (although this would soon be undermined through Crass’ anarcho-liberalism in a kind of sleight of hand). Music had to have a ‘message’, in what looking back meant a clear and obvious ‘message’ in the crudest, most didactic sense.

Anarcho had certainly gone beyond No Future! nihilism, but its projected future was bleak as the positivity there was waned: we thought that there would be a future, but it would be the grim nuclear winter future later represented in the TV movie Threads (1984), or that we would all die in a generalised, global Third World War, or we would be rounded up into concentration camps by a fascist state of the immediate future, or perish in some general ecological catastrophe. The only alternative seemed to be some sort of revolution of which we would all probably be killed. This combines naivety and pessimism to the extreme, although we had studied the Great War poets and all knew Wilfred Owen’s ‘Anthem for Doomed Youth’ (1917, published posthumously in 1920). I knew from my dad how in 1939 when he was thirteen the Second World War seemed like a great adventure and welcome break from normality, but how as the war progressed and he went further into his teens he would have to fight in it, which he did. Where I grew up near RAF Biggin Hill, still in the ‘60s a fighter base defending London, the Three Minute Warning sirens would be tested monthly, the test announced ahead in the local newspaper so as to avoid panic. So it was perhaps understandable that positivity fell by the wayside as the Sex Pistols’ No Future! morphed into Anarcho’s Bleak Future. Those fears we real, and understandable if you were young, sensitive, intelligent and well-read in the horrors of the twentieth century. A good friend of mine acquired a heroin addiction out of those fears and those fears alone. Indeed, even now I’m not sure those fears were misplaced, merely, perhaps, the things feared would come to pass a generation or two later than we expected. I think that’s why back then I didn’t get the Cramps: they had a different sort of ‘message’, a lot of which, to be fair to us, would have got lost in trans-Atlantic translation: at least in part this music is a holler of rage against California Governor Reagan’s (later US President) Reagan’s suppression of student radicalism, and the horror at the prospect of his Presidency. But they approached this more subtly and with ironic humour: subtlety was never Anarcho punks’ strong point, and as with Joy Division fans, humour was frowned upon. So what about the Cramps’ sound? IT’S FUCKING AWESOME, why the fuck didn’t I get that? I guess I saw them a sort of novelty act (the post-Punk world was full of them). My loss.

The Songs the Lord Taught Us, well it must have been The Lord of this World. Tribal-like drumming begins ‘TV Set’, rightly, us Punks on both sides of the Atlantic had it in for the telly, the goggle-box, the IQ crusher. The lyrics are kitsch Psycho Killer. After than that sheet metal guitar chimes in, with a raunchy, swaggering bass. There’s a bit of just about every rock ‘n’ roll song you’ve ever heard in there, ‘Great Balls of Fire’ pops in and says hello, and there’s Duane Eddy and surf, dark surf. ‘Rock on the Moon’, a Jimmy Stewart cover, has Lux Interior jabbering like a snake-handling Pentecostalist preacher jabbering In Voices: Robert de Niro surely tuned into this as he got into character for Max Cady in the 1991 remake of Cape Fear (1962), as he drowns at the climax of the movie he gives Lux a run for him money. ‘Garbageman’, what can I say? A Texas Chainsaw Massacre type VW campervan starts up, then this thing rocks: Duane Eddy’s sound is there, but gives way to Link Wray via Louis, Louis as the whole thing chugs on so powerfully. I’m reminded, as surely Lux and Ivy were of Kit, played by Martin Sheen in Badlands (1973), who first works as a garbage man before he sets off on a doomed relationship with Sissy Spacek’s Holly. ‘I was a Teenage Werewolf’ is pure swagger, ‘Sunglasses After Dark’ starts of as if it were on Songs That Crass Taught Us as a metronomic military drum leads the track out of discordant guitar feedback, but there the resemblance ends, sheet after sheet of chiming guitar, psychobilly riffs in increasing intensity, Link Wray’s ‘Ace of Spades’ (1965) surfing on acid atop the world-destroying tsunami wave we will see years later in the climax of Deep Impact (1998). Wow this is heavy shit! But fun too. Lux’s psychobilly rabid snake handling pastor is back on ‘The Mad Daddy’. Wow, and that’s just the first side. I could go on but I’ve said enough. Where was my taste back then?

Talking in Tongues, what was that? I’m not a Christian, but I’ve often thought it was to do with enthusiasm, the Greek etymology of the word meaning ‘to have a god (theos) in one’: snake bothering revivalists aside, I imagine what is described in Acts of the Apostles is like one of those enthusiastic drugged-up conversations one has with a group of people speaking different languages at a party, afterwards you can’t recall what language you were speaking at which time to whom, but meaning was made; so in their enthusiasm the apostles spoke in all those languages they had a passive knowledge of, or a speaking ability to haggle for stuff in the souqs of Judea – Aramaic, Arabic, Greek, Latin, Egyptian, Persian, Ethiopic and the like – but with passion and enthusiasm. But in the mouths of Evangelicals it become snake-handler’s snake-oil salesman gibberish. The world of critical New Testament Scholarship has moved on a bit from the hallucinogenic fertility rites of John M. Allegro’s 1970 tome The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross which Rorschach and Interior took in at Sacramento City College, today the field is contested between ‘mythicists’ who argue that Jesus never existed at all and the whole thing is a reworking of Classical pagan myth, and ‘historicists’ who argue for a historical ur-Jesus who was probably some sort of Jewish revolutionary or would-be liberationist from Roman rule – both agree that the New Testament can be read neither as history nor biography. But whatever the truth of that, The Lord, or some Lord, sure taught the Cramps some wicked songs. The Gun Club is new to me, I don’t think I’ve ever heard them before reading Season, but their sound seems cool: lighter than the Cramps, and punkier, as if the Buzzcocks met Surf met Rockabilly, until the Blues hits, and then Oh Wow! And when those guitars chime Oh Fuck Yes! With Lydia Lunch I’m the more familiar turf of NYC and London, her stuff is awesome and I’ve never lost touch with No Wave, anti-music, and performance art across the decades, so she doesn’t quite represent the fork in the road for me, her clear influences on Goth notwithstanding – my daughter knows Queen of Siam. Annie Bandez, aka Little Annie and Annie Anxiety provides a link between No Wave, Anarcho, and perhaps tangentially, Goth.

I run to my beaten up old pickup truck, clothes tattered and bloodstained, I managed to fight off the cannibals and zombies with what? A samurai sword? A chainsaw? I can’t remember. I’ve been scratched, or have I been bitten? I’m not sure which, I’ll worry about that later. I try the keys in the ignition. The engine turns over, but it won’t start. I scan around. My eyes fix on a Harley chopper, usually I like my bikes sportier, but beggars can’t be choosers. The key is in the ignition, the key-fob says Z, but Zed’s dead. So he shan’t miss his bike. I kick the engine over, it starts with a Harley’s ‘potato-potato’ 45 degree v-twin tickover; I stomp the agricultural gearbox into first gear, and blat-blat away along the winding road not taken, via the dark streets of ‘80s London to Goth’s Own County.

The blue Harley chugs up Soho’s Dean Street, I feel a bit of a prat: I’ve delivered everywhere in Soho, so I guess I must have delivered to the Batcave, although I can’t remember having done so. One might object that if I had delivered there I would have remembered it, but like I said, I’ve delivered everywhere in Soho, and beyond. For work like this the Harley’s useless, too much aggro kicking it over every five minutes for a start, and the power characteristics and riding position are all wrong. And unreliable: in their natural environment, Harley are cool, but not in traffic-choked inner London.

For this work a Japanese middleweight is what’s needed, not a sporty one, too much hassle, but one in a lower state of tune, a tourer or longer-range commuter, say a Honda CX500 or a Kawasaki GT750, both have shaft drive, so no drive chain, one less thing to worry about. Or perhaps an ex-police BMW 800 or 1000, also shaft driven, the sort of bike Punk biker me wouldn’t be seen dead on, but perfect for the job. This is one thing Patricia Morrison and I have in common I am a motorcycle despatch riding. I have been doing it a couple of years now, after straightening up following a very extended hard drugs binge that saw me homeless and totally fucked up. Twelve hours a day in the saddle, two hundred mile days are not unusual, three times that if there’s a Manchester and back in the afternoon; all year round in all weathers, all seasons, sometimes six days a week: Taxi Driver (1976), but on two wheels. But this is not like being a Deliveroo rider in the 2020s: imagine a London gridlocked with cars, there is no Internet, not even email, the nearest thing to instantaneous communication is a fax machine that can only send blurred text that has no legal status. Whether it’s the Inn of Court, advertising agencies or magazine publishers, film and TV companies, you name it, the only way to get documents, artwork or rushes from one part of London and beyond quickly is by motorcycle despatch rider: for the rider it’s a licence to print money (often off the cards) provided you know London, you know bikes, and you are prepared to put the hours in. But hey, getting paid for riding motorcycles, what’s not to like? Courier riding will go on to contribute the largest portion of the million or so miles I’ve ridden since 1974. Welcome to my 1980s, early in the decade I’d’ve been hip to any new club opening in Soho. But interest fades as days after day, week after week, month after month, year after year I put in the miles. At first Soho’s club scenes are parallel to my interests, then peripheral, then marginal, until eventually I have lost all interest. Mid-decade I am aware that there’s some new thing called ‘Goth’, but each to their own.

An image comes to mind of Lucretia, no makeup, dressed in baggy damp all-weather Rukka bike waterproofs, the whites of her adrenaline eyes staring from a coal-miner face sooted by hours of diesel fumes and road muck, hair soaked and matted, cold hands in half-finger under-gloves nursing a hot large cappuccino in a Styrofoam cup as her sodden bike gloves try to dry on the warm cylinder heads of her CX500, which stick out of both sides of the bike like Kirk’s ears. Snot drips into her coffee as she waits for the radio, ‘Mach 13.’ ‘Mach 13, over.’ ‘Lucretia, location, over.’ ‘Dean Street, over.’ We’ve got a Soho Square going to W2, roger that, over.’ ‘Roger that, W1 to W2. Over.’ It’s a tough job but somebody’s gotta do it. Despatch riding did me a favour in a way, it turned me from being a Punk-Biker hooligan into a proper motorcyclist. If it hadn’t, I might well be dead. See, this is the difference (apart from the fact that at the time of writing I am alive and he is long dead) between me and Sid: he could pose for a hundred or so yards on a crappy bike for a video, where as I can actually fucking ride.

I had kind of had it with music-based subcultures, perhaps its burnout, I was intensely involved in Anarcho, perhaps it’s fingers burnt: I had got in a very sorry state early in the decade. Must mostly I think it is this neurological tic of mine: I become passionately engrossed in a thing, then something clicks inside me and I drop it like a red-hot stone. Even though I’m only in my mid-twenties this isn’t the first time that’s happened to me. So now I’m writing about what I was partially aware of at the time, but certainly not involved in, or what I found out about later in the ‘90s, or discovered more recently. It’s a mixture of hard to recall memories, retrospective involvement, and of a senior citizen reading or listening to vinyl or YouTube.

I’m having morning tea as the glens fly by, I’ve been on the sleeper train, it’s sometime in between ‘Metal Guru’ (1972) is in the charts. I’ve always preferred Bolan to Bowie, even if the first Marc probably was the lesser talent of two great talents. Tyrannosaurus Rex’s My People …. (1968) has long been in my record collection, so has The Stooges (1968), gifted to me by my dad along with much else from his record shop, he’d come home and toss some vinyl at me ‘It’s not selling, but it looks like the kind of crap you’d like, Lad!’ I’m with my maternal grandmother, when in the late ‘60s my parents started to go to sand sea and sun summer holidays in then exotic places like Ibiza, I decided it wasn’t for me, so I went on Grand Tour type trips to Italy, France, Germany, and Austria. But this year it is the Highlands and Islands. She looks at my nails, ‘take that stuff off’, they are varnished purple, ‘some people might think it’s effeminate’. She’s broadminded so I talk to her about it. Was it only in Scotland that people thought it effeminate?

So Soft Cell. It’s odd that the pun from the world of advertising has been largely forgotten, a sign perhaps that the duo had become sufficiently a subcultural power in their own right not depend for their fame on a mere witticism. I had Mutant Moments when it came out, but not long after their awesome cover (1981) of Gloria Jones’s (the driver of Marc Bolan’s purple 1275GT Mini that fateful night in September ’77, Car Crash/Carcass) ‘Tainted Love’ (1965) brought a subculture into the mainstream, very much into the mainstream as it was everywhere on the radio, a decade on from T Rex’s highwater marc gender was once again being bended on Top of the Tops, but by the time of their awesome cover of Suicide’s ‘Ghost Rider’ just a couple of years later Soft Cell was off my radar, which was by then more tuned in to Nicholson’s London Streetfinder, which was easier to reference in a hurry than the A-Z, although the latter had its strengths too. A marc of how much I had changed (Almond will suffer horrible injuries in the City on a bike in 2004, and go on to raise money for brain injuries, strength). Soon I’d commit it all to memory, like a London cabbie’s ‘Knowledge’ – I knew I was a serious courier when, through gritted teeth a cabbie asked me where to find an obscure mews, for all I know he was Amy Winehouse’s dad); despatching at that level requires 100%, leaving nothing in reserve. A yelpy and discordant existential cri de cœr with a catchy beat, whip-snap electrics, echo, and a saxophone primal scream the ‘Ghost Rider’ cover reminds me a bit of the Pop Group, but snappier more polyphonic, and greater depth, it’s fucking awesome, but I’m catching up with it on YouTube. Likewise Foetus, I was of Foetus in the day but that was about it. It sample ‘Nail’ by Scraping Foetus off the Wheel (1985). What I was missing! Why was I missing it back then? I knew of the Meteors from ’79, but the whole psychobilly thing passed me by? Why? Partly, I think, because by the early ‘80s Anarcho had embraced DIY with a vengeance, to the extent that it became impossible, the claims of New Model Army notwithstanding (and I still see that as just a claim), for something to be Anarcho if it wasn’t DIY. We therefore tended to see anything that was promoted in the mainstream music press is essentially fake, just one small step away from created-in-a-boardroom boy bands. Perhaps there was some reason for that, Gary Bushell’s construction of his Oi! pet project and fuck the fascist consequences attitude was an example, the New Romantics (who Unsworth also seems to dismiss, I think correctly, not to confuse that with Goth) another, media created subculture. But this Anarcho-DIY purism, in a sense also a kind of puritanism, blinded our eyes and stopped our ears to some awesome music, simply because it was promoted in Sounds, the New Musical Express, Melody Maker, The Face, even Jamming! or Vague for fuck’s sake! My lack of engagement with Psychobilly is an example. My loss: I’D’VE FUCKING LIKED IT! We Anarchos took music too seriously as an instrument of change, originally a facilitator of solidarity, creativity, and organisation, the music became the change: if a song was sung about an issue the mentality emerged that the issue was halfway to being changed. Goth was to develop a means of being musically and creatively subversive, but without that naivety. Anarcho was becoming like a cult, which is when and why I jumped ship. We took music too seriously as an instrument of change. Unfortunately I dumped the entire music scene of that time, Foetus along with the bathwater.

The cliché has it that the 1980s were a materialistic decade, certainly that’s what Unsworth’s Wicked Witch, Thatcher’s apologists and nostalgists, and her backers in the right-wing press (that is nearly all the UK press) would have us believe. I’ve never been a particularly money-motivated person, but for what it’s worth in July 1985 I earned the most money I ever earned in a day, about £2,500, around £7,000 in 2023 money, according to the Bank of England’s inflation calculator. An investment banker or hedge-fund manager would hardly notice that, but it’s the most I’ve ever earned. Patricia said she had earned more despatch riding than she ever did as a Sister. But it was soul destroying work, on the Honda VT500 (a longitudinal v-twin, the V along the frame like a Harley, the Honda CX was a transverse v-twin, V across the frame so the heads stick out each side, like a Moto Guzzi, like Kirk’s ears) up and down the A404 constantly from 8 a.m. all through the day, all through the gig, between the Mail on Sunday’s headquarters on Carmelite Street, EC4, off Fleet Street, and old Wembley Stadium. A team of eight of us ferried reels of paparazzi film of the stars arriving at the event, the event itself, the stars leaving, then following them to Annabel’s night club in Mayfair until the wee hours taking back yet more reels of film for the late editions. Of course I didn’t give a fuck about Live Aid, but a 15 year-old cousin was delighted when I dropped her off with a pass in the VIP area, picking her up a couple of hours after the gig had ended then ferrying her home on the way back to Carmelite House.

The second half of the 1980s was one of two times in my life when my significant other was a guy. I had met W at the 121 Anarchist Bookshop. He was older than me, an austerely intellectual, all those more impressive because, like me at that time his knowledge was entirely autodidactic. He had a love of experimental film and music, and we would stay up all night listening and watching as we chain-smoked joints of hashish and when we could get it raw opium. I got him into despatch riding, and he would work the six months of good weather in London, then spend the next six months travelling. The first time was down Africa from Morocco to Cape Town, then three different trips exploring India, I would accompany him as far as the Middle East. We lived in squats, one was in Streatham, an old man living alone had died there and been left undiscovered for months. When we broke in it still smelled of decay, and there was a body shaped stain where the corpse had lain. We made it homely, and our all-night discussions started with anarchism but drifted inexorably to a search for the transcendent. W loved India and was as strongly attracted to the Vedic traditions as I was to Judaic and Islamic mysticism. Once he brought me back a massive black clay chillum from a Shivite temple, styled like a snake with indented scales it had real garnets for eyes which glowed in the dark when you got the suck just right. In 1988 he stayed at the Bede Griffiths’s (1906-1993) Shantivanam Ashram in Tamil Nadu, where Roman Catholicism was practiced in a ‘Hindu idiom’. He converted there, taking the conversion name Jyoti, meaning ‘light’, and stayed a whole year. I used to send Kabbalistic, Sufi, and Shi’i stuff for their library. On his return to the UK, armed with a letter from Griffiths, he gave me all his belongings, his music and book collection and a nifty little black Honda CB12T (the delightful sporty little twin, not the CG125 single), which was great for town work and great fun to ride. W shortly afterwards entered a Benedictine monastery as a novice following a very strict contemplative rite. I never saw or heard of him again. Heartbroken I continued to ride. I also tried, in imitation of W, to live a pious life of faith, but in a different religion. It lasted a few years, including a short-lived marriage to a K, a Franco-Arab woman, ‘my limbs are like palm trees. Swaying in the breeze / My body’s an oasis, to drink from as you please’; but me and K were moving in opposite directions. One day, I was delivering to City University in EC1. There was an NUS picket and a student handed me a leaflet about the threatened replacement of student grants with loans. Aged 30 I knew I had to bite the bullet: I entered a four-year degree as a mature student graduating in 1993 with a 1st in Arabic and Hebrew, studying a year’s language immersion in my third year of four at the American University in Cairo and the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. By 2001 I had a PhD in Middle Eastern comparative literature. From then until 2011 I worked as an academic in the Middle East. My punk conscious reawakened after witnessing the murderous suppression of one of the Arab Spring revolutions. Students I had taught had been killed. My 1980s were rather a flight from materialism than a headlong rush into it. In that flight, the music was forgotten.

I met M not long after I graduated with my first degree, when she was a habituée of the Slimelight club, she had a thing about tall, intellectual Goth and Metal guys. My attempt at religious faith in tatters, and ever given to overcompensation, I was kinda Punky-Metally, but in 1994 I had only a vague idea of what had happened with the music since 1984, and was on a steep learning curve. Through her I got to catch up on the Cure, engage with the Cult, and the Sisters of Mercy. As a toddler our son Benjamin (born 1997) used to do a kind of proto-dance to ‘Temple’ in his nappy. M and I were still listening to it in 1999. So from Season I learn about the backstory to the SoM, new information to me after all this time: before Andrew Eldritch there was Andy Taylor, not from Leeds but from Ely. All this was news to me until I read Season, although I’m sure the information is easily available online I’d never thought to look. As I would later become he was a linguist. Bored, perhaps understandably, at reading French and German at Oxford, he moved to Leeds to study Chinese. In 1978. In the day I saw plenty of Leeds bands quite often: the Mekons and the Gang of Four, both of whom I think are still going; Scritti Politti (Green Gartside is a favourite of M’s), Delta 5, the Three Johns. But I’d see them in London, some of them I would see supporting London bands, some I would see at Rock Against Racism gigs. I’d also quite often travel up to Leeds, but never to see Leeds bands, rather when I was following London bands. I had that odd metropolitan parochialism: to me at that time Punk had an epicentre in NYC and a ground zero in London, anything from anywhere in the US or UK seemed a provincial catch-up, bar Manchester. How stupid and arrogant of me. I had no idea that Leeds had got a shot of Punk rock straight from CBGBs circa 1975 via Jon King and Andy Gill. No idea at all. Although I would visit Leeds fairly often I knew nothing of the F-Club nor Futurama, all those bands were merely ‘from Leeds’, as in ‘not bad considering they are from Leeds.’ When I started to understand that Goth was I thing I ‘naturally’ assumed it was a London thing, ‘Northern Goth’ had something to do with Whitby, which I had heard about from Bram Stoker’s novel Dracula (1897), and from the Prospect of Whitby pub on the Thames at Wapping. From 1976-’78 I was London fixated, 1979-’82 I was Anarcho-obsessed; given my later life history I am amazed at the narrowness of my horizons at that time.

My next extended Toxic Grafity reflective review will be Richard Cabut’s Looking for a Kiss (2020, 2023); but yes, the whole intersect between his Positive Punk, early Goth, and Anarcho is fascinating – writing this it seems ever more incroyable that I never became Goth, or at least was part of early or proto-Goth. Cowpunk? Rockabilly I get, but ‘Cowpunk’ only brings to mind a Vivienne Westwood t-shirt, or perhaps the Meat Puppets. Where was I to have missed Cowpunk? I never really related to The Pack or Theatre of Hate. ‘King of Kings’ (1979) was a bit of a chimey rocker, but there’s that nasty white and red crusader cross on the cover, and the lyrics read like a nasty Christian Right rant delivered by someone who didn’t even understand Christianity very well. ‘Spear of Destiny’? Give me uMkhonto we Sizwe any day. Maybe be I’m judging Kirk wrongly, on hearsay, rumour, even slander? Well, he does have stick-out ears, but I was born with Dracula teeth, so we can’t all be perfect! But (Southern Death) Cult, now they’re a different matter. I never got the ‘Southern Death’ part of the Bradford band’s name until I read Season, then London-centric me wouldn’t’ve done, ‘the place where all Britain’s authority lay’. Nor did I pick up on how Aki Nawaz (Haq Nawaz Quraishi – the Quraish were the Arabian tribe from whom the Prophet Muhammad arose and there is a Sura, ‘Chapter’ in the Qur’an called ‘The Quraish’) and Killing Joke’s Jazz Coleman were post-Punk’s and proto-Goth’s South Asian heritage standard bearers, ‘That time is running out / Nagasaki’s crying out’, ‘Moya’ (1983) is so much of it’s reheated Cold War time, like Crass’ ‘Nagasaki Nightmare’ (1982), but less experimental, more harmonious. Both are very fucking good, up there with Frankie Goes to Hollywood’s ‘Two Tribes’ (1984), and Nena’s ‘Neunundneunzig Luftballon’ (1983) in saying what needed to be said at that Greenham Common time.

I shan’t say too much about The Mob, New Model Army, and UK Decay here, as that will segue into articles I want to write soonish about Anarcho. Unsworth mentions Crass as the origins of ‘Goth’s own militant tendency’: I can see her point, and it’s one I’d like to explore in greater depth another time. I knew the band very closely from 1978-’82; for me at least they drifted from being a very collegiate band-collective with radically collaborative artistic decision-making and close roots in actual anarchist movements, to becoming towards the end something of a guru-led cult wherein adherence to a highly individualistic and ultimately, if perhaps unconsciously, rightist form of anarcho-liberalism became a kind of internal discipline. In the 2020s much of American ‘anarchism’ is highly individualistic and expressly far-right. The band floundered on that rock. That the guru figure now tends to be seen as the figure in Anarcho needs, I think to be questioned. Rimbaud acted like a kind of St. Paul to Anarcho’s Christianity, taking leadership of the movement in a deniable way, changing it from the inside, neutering it, making it something other than it originally was, rendering it harmless in its individualism: with no disrespect at all to those who were involved, some of whom are still even to this day involved, in peace convoys, DIY record labels and fanzines (I produced one!), vegan co-operatives and permaculture, Alt. Lifestyle was never going to change what Thatcher, Reagan, Murdoch, and their successors would have instore for us. Indeed it could be easily accommodated or co-opted, or else supressed if it got too uppity.

I would suggest that the Poison Girls, at least in their early Brighton and Epping configurations, are perhaps better candidates for Goth’s own militant tendency: radically feminist but also leftist-anarchist, Vi Subversa (Francis Sokolov, 1935-2016) channelled her inner witch, her Hectare, her Lilith, her Afroditi with both ardentness and humour, exposing the darkest aspects of capitalism, patriarchy, and the human psyche in general while retaining an optimism of the will and the spirit, all this explored in a wide musical range that had one foot in Punk and Rock ‘n’ Roll, and the other in the experimental and sound-artistic. All packaged in the boldest red and black artwork that bought wise women and cunning folk in creative conversation with dissidents and anarchists, feminists in floral skirts, persons unknown. And they really did raise the consciousness, in the feminist sense, of a generation of young punks including, perhaps especially, the men. Vi played her final gig in Brighton in 2016, which I could not see as my dad lay dying in hospital in the same city. RIP old friend and mentorix, RIP dad.

‘Mach-35, Mach-35.’ ‘Mach-35, we’ve got a Liverpool coming up if you’re up for it? Over.’ Liverpool? That’d be a cool £220, minus petrol and wear and tear on the bike. I’ve already made £120 in London this morning. The day’s looking good. ‘Mach Base, roger that, over.’ ‘Warner Brothers, Theobalds Road in thirty. Some cover artwork for a band to check out. Over.’ ‘Roger that, over.’ I live in Rotherhithe, SE16, on the border between Zone 1 and 2. Twenty minutes to get there and swap bikes, another ten or fifteen to PoB. The Honda 250RS single cylinder is great for town, light, reliable, economical, but I need something more substantial for long distance. Doing this job you need to keep several bikes on the go, ‘Metal is tough / metal will sheen / metal won’t rust when oiled and cleaned’. The long-legged Suzuki GS850 tourer, the detuned ‘cooking’ version of the super-fast GSX1100R; but the 850 was shaft drive, fitted with a screen, but perfect for the job. I nip home, swap bikes, and bungee the flat artwork carrier on securely. Clear of central London, I head on up the left-hand path that is the M1-M6. A record is a complex thing, the product of many different kinds of labour. You seldom know what is in the packages you deliver.